The murder shocked the African American community and resulted in near riots. President Kennedy issued a statement condemning the killing, and the FBI took control of the search to find Evers’s murderer. Within two weeks, a fertilizer salesman named Byron de la Beckwith (1920–2001) was arrested for the crime. The evidence against Beckwith seemed overwhelming: the rifle scope from the alleged murder weapon had one of his fingerprints, his car was seen in the area near Evers’s home at the time of the killing, and he had asked two cab drivers for directions to Evers’s home just days before the murder. In addition, Beckwith was a member of the White Citizens Council, a white supremacist organization. However, Beckwith produced witnesses—including two police officers—who testified that he was far away from Evers’s home at the time of the murder.

Beckwith’s murder trial began in 1964. In court, he was confident and friendly with court officials and even with members of the jury, who were all white males from the area. The governor of Mississippi visited Beckwith during the trial, and some accounts state that the jury witnessed the governor hugging the defendant in the courtroom. For the African Americans in attendance, however, Beckwith showed only contempt. Despite the evidence against him, he appeared certain that his white male peers on the jury would find him not guilty. Both the prosecution and defense were surprised when the jury came back after over thirty hours of deliberation and told the judge that they could not agree on a verdict. They were split nearly down the middle with no hope of reaching an agreement—a situation known as a hung jury.

Because the trial could not be completed, prosecutors were free to file murder charges against Beckwith a second time, which they did. This led to a new trial in 1965, which also ended in a hung jury. Rather than risk acquittal with a third trial, prosecutors chose not to file charges until more convincing evidence arose or until conditions improved enough for African Americans that they could be sure to receive an impartial jury. Unlike other crimes, cases involving murder do not have to be taken to trial within a certain period of time, known as a statute of limitations. Prosecutors could wait as long as necessary to guarantee a fair trial. It finally took place more than thirty years after Evers’s murder.

Unlike the juries in the first two trials, the jury for the new trial was at last representative of the population in Jackson: it contained eight African Americans and several women. New evidence included witness testimony that Beckwith had bragged about committing the murder. In 1994, at the age of seventy-three, Beckwith was at last found guilty of murdering Evers; he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. He died in prison in 2001.

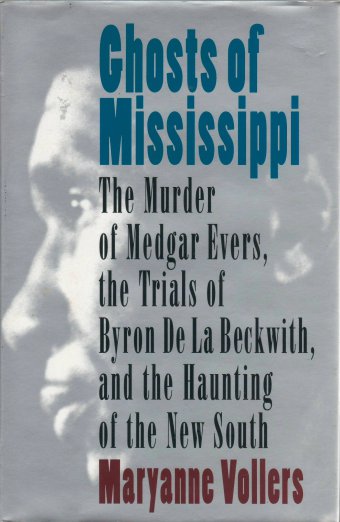

In 1996, director Rob Reiner (1947–) released the film Ghosts of Mississippi, which details the murder of Evers and the long road to justice. In the film, Whoopi Goldberg (1955–) portrays Evers’s widow Myrlie, who continued to push for a third trial even after decades had passed. Evers’s two adult sons appear as themselves in the film, and his daughter plays the role of a juror. After the successful trial of Beckwith, Myrlie Evers-Williams (c. 1933–) was selected as chairman of the NAACP. She served as chairman from 1995 until 1998, continuing the activist work of her former husband. (1)

Ghosts of Mississippi: The Murder of Medgar Evers, the Trials of Byron de la Beckwith, and the Haunting of the New South by Maryanne Vollers. The book is available from the library.

After three trials and thirty-one years, Byron de la Beckwith was found guilty of murdering Medgar Evers, the legendary Mississippi civil rights leader. Beckwith, who was seventy-three years old and suffering from poor health when the jury announced its verdict, was sentenced to life in prison for the killing. Maryanne Vollers’ Ghosts of Mississippichronicles the social, political, and legal consequences of the Medgar Evers/Byron de la Beckwith saga, spanning seventy of the most chaotic and troubled years in Mississippi history. Vollers opens her book with Beckwith in his jail cell awaiting his third trial as he entertains several friends and relatives with animated stories and racist jokes. Beckwith is shown to be a confident exhibitionist who thrives on both attention and animosity. (Read more)

Learn more about the trials here.

New Medgar Evers Trial May Help Mississippi Cleanse Its Past

In late 1989 Bobby DeLaughter embarked on what looked like a mission impossible. His job: to reassemble the 27-year-old murder case against Byron De La Beckwith, the white supremacist who was tried twice in the 1963 assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

DeLaughter, a white Hinds County assistant district attorney who was in 3rd grade when Evers was shot, set off on his assignment with little information and less hope. He had no murder weapon, no list of previous witnesses, no transcript of the 1964 trials.

(1) “Evers, Medgar (1925–1963).” African American Eras: Segregation to Civil Rights Times. Vol. 1: Activism and Reform, The Arts, Business and Industry. Detroit: UXL, 2011. 12-16. Gale Virtual Reference Library