‘A genius’ — Medgar Evers College Latino Heritage Month Committee to honor legend Eddie Palmieri

By David Gil de Rubio | dgilderubio@mec.cuny.edu

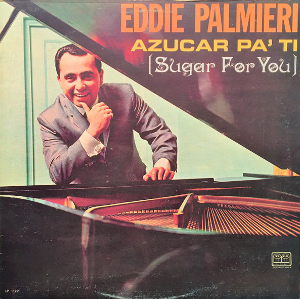

When Eddie Palmieri passed away on August 6, 2025, the world lost far more than a totemic musical presence who not only turned Latin music on its head, but used his art and influence as a means of advocating and fighting for the oppressed.

At a time when former colonies were fighting for independence in the African continent, Palmieri drew the unwanted attention of the FBI and CIA for his 1965 album Mambo con Conga is Mozambique.

During the same era, the native New Yorker was using his craft to convey his beliefs via outings like 1969’s Justicia, which addressed inequality and discrimination while fusing salsa dura and more experimental jazz arrangements. It’s a part of the late salsero’s personality longtime friend and Young Lords co-founder Mickey Melendez is well familiar with.

• • •

A tribute to Eddie Palmieri will be held on Friday, October 10, from 1 to 5 p.m. at the AB-1 building. Click here to register.

• • •

“For me, I am grateful that I walked this Earth and met a genius,” Melendez said. “I knew Eddie for 60 years and I can truly say he was a Renaissance man. He was not just a musician, but someone who carried genuine interest in a variety of subjects. He could probably talk about anything and everything. It wasn’t just about politics or the arts. It was about being grounded in our reality as marginalized people, as Puerto Ricans. I’m not so sure that people would be surprised by that.”

Melendez, who got his start as a teenager as part of the Plebeians Fraternity promoting Latin music shows in numerous clubs including the Yorkville Casino on East 86th Street grew to appreciate the musical innovator his late friend was.

“I remember going up the stairs of this club, walking into this hall, looking to my left and there was Eddie Palmieri Perfecta, the first band that he had,” Melendez explained.

“Eddie invented salsa. He rethought it. Up until that time it was just big bands led by people like Machito, Tito Rodriguez, Tito Puente and you had artists like Vicentico Valdés, that followed the format of the big band sax section and certainly a trumpet section. On the other side of stuff, the young guys here were already listening to Cuban music.

“The charanga craze of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s is basically two violins and a flute. Eddie flipped it and put in two trombones that were blaring and had a swing in what I call getting your ‘bones music. You either had the big bands, the charanga sound then you had this emerging sound of Eddie Palmieri.”

Ramiro Campos, who is Palmieri’s son-in-law and also a professor of geology at Hunter College and an adjunct professor at Medgar Evers College, already knew of Palmieri’s musical legacy, but was struck by his role as a patriarch the first time he met him at an Irish pub.

Ramiro Campos, who is Palmieri’s son-in-law and also a professor of geology at Hunter College and an adjunct professor at Medgar Evers College, already knew of Palmieri’s musical legacy, but was struck by his role as a patriarch the first time he met him at an Irish pub.

“I remember my future wife Ileana, his daughter, was having drinks with him,” Campos recalled.

“I’m not exactly sure why he was at that pub but it was somewhere in Midtown. I just thought to myself that this was the kind of dad I need to be. I want my daughters to want to hang out with me when I’m older. That was the kind of dad Eddie Palmieri was.”

As Campos got to know his future father-in-law better, he also grew to appreciate the man whose depth went far beyond music. A big part of what Campos experienced was seeing how Palmieri went through life as both a student and teacher, who was always seeking knowledge about myriad subjects while deferring to those with a greater understanding of said subject.

And also as an old-school salsero who taught master classes at Rutgers University and was quick to hold the line in terms of tradition.

“When it came to things he didn’t know, he always deferred to people who knew things,” Campos said. “The other thing that was a huge part of Eddie’s personality was that he had an appetite for learning about history and philosophy. He was really big on that. I wish I had more time with him to really go into that. He was really fascinated with Aristotle, Socrates and the old-time philosophers.

“I wish I could have brought him up to the 21st Century.”

He added, “I will say there was a streak to him when it came to forms of music, where he as the elder statesman, he really had to let everyone know how to do it right, this is how we do it and why we do it. This is why the structure should be respected and all that kind of stuff.”

When it came to social justice, Palmieri wasn’t content to sit by the sidelines. One particular instance of his joining the fight came when 27 Puerto Rican activists seized the Statue of Liberty on October 25, 1977, to protest the imprisonment of five U.S.-held Puerto Rican political prisoners. In the process, the Puerto Rican flag was hung from the statue’s crown, garnering a significant amount of press coverage.

Melendez was one of those 27 activists who were arrested, jailed and fined $100 a person. Palmieri saw the story on the news, contacted former Young Lord-turned-journalist Pablo Guzman to find out more about what happened and how he could help. Guzman told him about the $2,700 in legal fees and Palmieri immediately volunteered to play a benefit show to raise money for the 27 who were charged.

Melendez was one of those 27 activists who were arrested, jailed and fined $100 a person. Palmieri saw the story on the news, contacted former Young Lord-turned-journalist Pablo Guzman to find out more about what happened and how he could help. Guzman told him about the $2,700 in legal fees and Palmieri immediately volunteered to play a benefit show to raise money for the 27 who were charged.

“We got together and did a benefit for the Statue of Liberty 27 at Hunter College at $3 a pop,” Melendez said. “Journalist Gerson Borrero was the MC and the place was just overflowing. People were sneaking in through the exit door because they couldn’t get in. We made so much money that we paid for the 27 people that were fined. With the extra money, Eddie decided to play free shows at some prisons, so we did Bedford Hills, Greenhaven and Riker’s Island. When he was asked why played these prison gigs, Eddie said, ‘I have a lot of friends there that I haven’t seen in a while. And besides that, it’s a captive audience.’”

That consciousness about the less fortunate and the historical trials and tribulations people of color went through was always front and center for Eddie Palmieri. And it’s something Campos saw on a regular basis.

“Eddie always tried to keep it Black,” Campos said. “He always honored the African legacy of music. He was definitely somebody who felt you can’t forget about civil rights or the struggles. You can’t go backwards. I think his legacy is that in his mind, he honored all the people who died and suffered during the Middle Passage and that he was continuing this legacy of resistance and how that changes during the different decades and centuries. His legacy would be one of civil rights and social justice.”

When it comes to Eddie Palmieri’s musical imprint, Melendez didn’t hold back in assigning the place his late friend held in history.

“We can never forget how Eddie contributed to the development of our music and culture in the diaspora,” Melenedez said.

“He was like our Bach, Chopin, Beethoven, Rafael Hernández Marín and Ladislao Martinez all put together. That I think is his legacy.”